MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn questioned the NCAA’s ability to manage college athletes after the ‘lack of consistency and transparency in the Wiseman case’ during a hearing on Tuesday afternoon.

Blackburn said the way the organization handled the situation completely eroded its ability to handle the issues of player benefits.

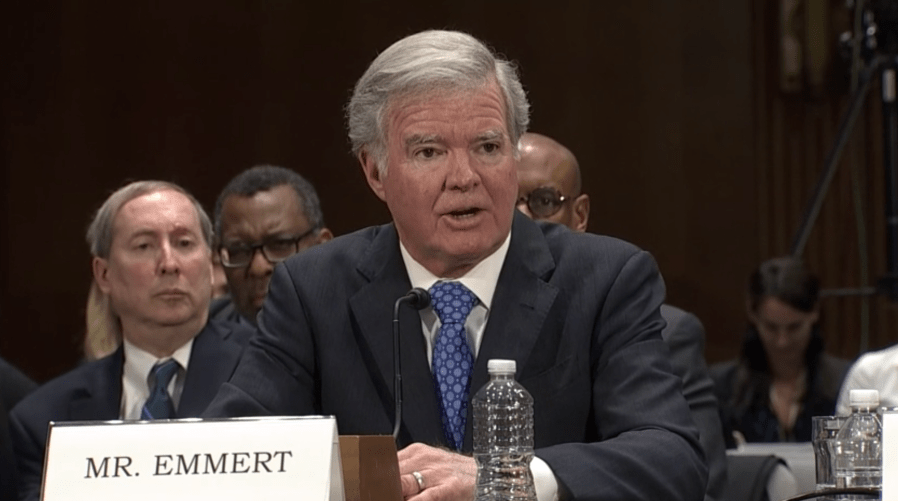

“I will tell you, I think there has been little if any transparency between James Wiseman, the University of Memphis and your organization,” Blackburn said to NCAA President Mark Emmert.

James Wiseman was a star player for the University of Memphis Tigers who left the school after the NCAA suspended him for 12 games.

James Wiseman announced in December of 2019 he would be leaving the University of Memphis to prepare for the 2020 NBA Draft.

Head coach Penny Hardaway gave Wiseman’s family $11,500 to move to Memphis while Penny was the head basketball coach at East High School. The NCAA said this was a violation because Hardaway had donated $1 million to the University of Memphis nearly a decade ago, which made him a school booster.

Hardaway would not become the head coach of the Memphis Tigers until 2018, a whole year before James Wiseman would commit to play college basketball.

“When you talk about student academic success while being in fairness, this has been a failure for you all and the way you handled this,” Blackburn said. “We’re looking at a time where now student athletes are going to be trying to figure out if they are better off going to the pros and skipping college because of situations like James Wiseman.”

Blackburn questioned Emmert on why the Wiseman family and the university were not told about the concerns over Hardaway’s donation sooner.

“I’m not involved in the details enough of that particular case to answer your specific question,” Emmert answered.

“But you’re the CEO,” Blackburn replied. “When there is a lack of transparency or subjectiveness, the objectivity should come to you.”

The purpose of the hearing was for Emmert to urge Congress to put restrictions on college athletes’ being able to earn money from endorsements. He said federal action was needed to “maintain uniform standards in college sports” amid the recent laws passed in California and under consideration in other states.

Last fall, the NCAA said it would let players benefit from the use of their name, image and likeness. The organization says its working on new rules, which will be revealed in April. Under the NCAA’s timelines, players can start benefiting from endorsements starting in January of 2021.

Big 12 Commissioner Bob Bowlsby supported the NCAA’s concerns saying endorsement deals for athletes would have a negative impact on recruiting with schools and boosters in states with athlete-friendly laws using money to entice plays to sign with certain schools.

An Associated Press investigation found the NCAA, the Big 12 and Atlantic Coast Conference spend $750,000 last year lobbying on Capitol Hill in an effort to voice their concern that rules need to be in place for athlete endorsements to avoid destroying college sports as we know it.

NCAA critics already believe recruiting is corrupt, pointing to the federal criminal case involving shoe companies paying basketball players to attend schools they sponsor — and that letting players earn endorsement money won’t create the major problems the NCAA predicts.

The senators agreed, crossing party lines, that athletes should have access to endorsement opportunities and that some regulations are necessary.