MEMPHIS, Tenn. — A Memphis police officer’s file shows repeated complaints of excessive force, including him wrapping his arm around a teenager’s neck.

In a partnership with the University of Memphis Institute for Public Service Reporting and The Daily Memphian, we are working to uncover incidents of excessive force and help find possible solutions.

What started as a traffic stop on Staten Street in September 2016, turned into a chase when one of the men in the car bolted.

Backup was called to deal with two people who stayed with the car. One of them was taken into custody.

A third person was a juvenile, which is why MPD blurred some of the video.

She was 15 years old but lied to officers and told them she was 10 years old.

What happened next is what was called into question. Jackson approaches the girl, puts his hand on her neck and says, “Don’t do that.” The girl begins screaming.

The teenager filed a complaint with MPD’s internal affairs, stating Jackson “placed his right arm around her neck” and she “was not able to breathe.”

Another officer’s body camera shows a different angle. You can see Jackson’s arm wrapped around the teen’s neck. The video goes out of frame, but comes back as Jackson puts the teen in a squad car.

“I’m not choking her,” Jackson says in the video.

Jackson told internal investigators, “There was space between his arm and her head and chin.” He felt she “resisted” and “posed a deadly threat,” because she was “kicking her legs and screaming.” He says he didn’t know if she possessed a weapon.

“She didn’t lose any type of breath. She was yelling the whole time,” said one officer at the scene.

Other officers at the scene defended Jackson’s actions, and Jackson defended himself to the teen’s father.

“The law states I can use force if necessary and if she wants to act a fool, I can use necessary force to put her in that car,” Jackson says.

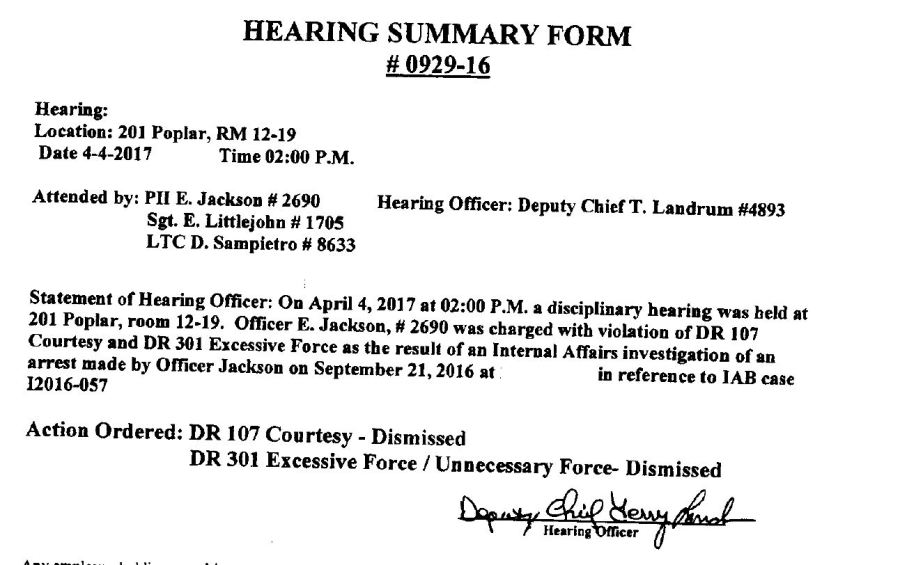

MPD’s internal investigation and hearing ended with Jackson in the clear.

The teen then took her case to the Civilian Law Enforcement Review Board, CLERB for short. It’s an independent board that also investigates complaints of police misconduct and makes recommendations to the director.

WREG found the letter the board sent to the police director, taking the teen’s side.

They recommended anger management training. They added “the dismissal of charges hinged on a technical definition of chokehold.”

For decades, MPD policy has stated choke holds of any kind are strictly prohibited. That includes “hands, arms, knees, feet or one’s body weight to restrict a subject’s ability to breathe.”

The police director stated that didn’t happen, writing, “I reach this conclusion by noting (the teen) continued to yell and scream.”

He felt the teen was “non-compliant,” and Jackson’s actions “were within policy.”

CLERB letter to police director

Officer had previous complaints

Evelyn Lott said her son encountered Jackson in 2000 at Carver High School.

MPD records state her son, 15 years old at the time, wasn’t paying attention to Jackson’s presentation about being a part of MPD.

A coach in the classroom told internal investigators that Jackson and the teen got into it, and he saw Jackson put his “arms around the student’s neck” when he took him “into the hallway.”

“It’s sad. We are trying to raise our kids to respect those officers,” Lott said. “It could’ve been handled a whole lot different. They are here to protect and serve. Him being a man, he should not have put that much force on him.”

Jackson was suspended one day for unnecessary force against Lott’s son.

It was one of the only reprimands Jackson received, despite six complaints about his conduct or excessive force. Three were claims of choking.

His actions were ruled justified, or internal investigators couldn’t find the person or evidence to back it.

One of those cases was in 2017 on Kenny Crest Drive. A man claimed he and Jackson got into it when he was accused in a robbery.

He says Jackson “started choking him with both hands around his neck” and “slammed him on the car.”

But there wasn’t any video to prove it, since Jackson never turned on his body camera. He got a written reprimand for not doing so.

This case was also reviewed by CLERB.

“We said it was unacceptable for a police officer to not have a camera on,” said interim CLERB President Ricky Floyd.

He was on the board at the time, but isn’t sure if the past president followed up.

MPD said complaints made against officers are thoroughly investigated. Then, the hearing officer looks at internal affairs’ findings, as well as the officer’s history and explanation, and determines if charges should be upheld and what the corrective action will be.

The case on Staten never went to the district attorney for review.

The teen was given a juvenile summons. She told us in a Facebook message she never saw the body camera footage. She didn’t get back to us about an on-camera interview.

Jackson remains on the force.

WREG reached out to the department to see if he had a statement, or it had a statement on his behalf, but we never heard back.

MPD’s full statement about how the complaint process works:

ISB thoroughly investigates the complaint at hand. Past incidents would not come into play when reviewing a current complaint. ISB does not determine what, if any, corrective action should be rendered. ISB provides their findings of a case and then, the findings are passed along to a hearing officer. The hearing officer then reviews the findings and past incidents. The officer is provided a hearing date where he/she will meet with the hearing officer and go over the allegations. Officers have due process and they are allowed to provide additional information and explanation during the hearing. It is the hearing officer’s duty to determine if the suggested charges by ISB should be upheld, and if so, what that corrective action will be.

About this series

One reason WREG, The Daily Memphian and the Institute for Public Service Reporting teamed up was to help defray the costs for internal files and body camera footage– some totaling $1,000.

This video cost $252. MPD said the price includes retrieving and redacting information required by law.