MEMPHIS, Tenn. — A handcuffed man was sprayed with pepper foam and left in a Memphis Police car with the windows rolled up, and police body cameras captured the incident.

WREG uncovered the case in a collaborative investigation with the University of Memphis Institute for Public Service Reporting and The Daily Memphian, working together to uncover excessive force incidents and help identify possible solutions.

Body camera footage from the incident is now leading to discussions about mental health.

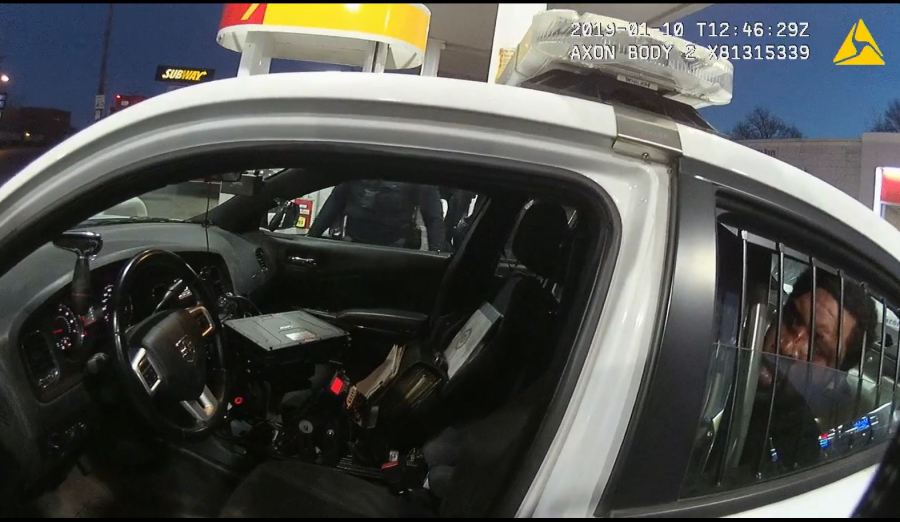

Below: Police body camera footage shows Drew Thomas’s arrest by Officer William Skelton.

It happened on Jan. 10, 2019 a few miles from the airport. Memphis Police got a call that a man who had been banned from a gas station on Airways was causing a scene.

“I said you’re under arrest m**********r! Get the f*** over here!” an officer says.

In the video, Drew Thomas asks the officer what he did. Officer William Skelton tells him that he vandalized the inside of the store.

Once Thomas is in the officer’s car, Skelton says Thomas kicked the door.

Skelton tells Thomas, “Kick my car again, I am going to foam you. You understand, ****head? I will spray the f*** out of you, you worthless piece of incestuous s***.”

That threat of pepper foam is then carried out. Skelton told MPD Internal Affairs that he used the foam four times to get it “in his face.”

“I foamed the f*** out of him,” Skelton says in the video.

Thomas’s legs are then restrained, and as he lays across the back seat, you can hear his request for the windows to be rolled down.

“For you? Hell no,” Skelton says.

Drew Thomas (at right), who family says is bipolar and schizophrenic, is seen in the back of a Memphis Police squad car on Jan. 10, 2019. Video shows an officer pepper spraying him, shouting expletives and refusing to roll down the car’s window.

Drew Thomas (left) and Officer Skelton

MPD records state Skelton didn’t open the window, despite policy that officers must take “necessary steps” in safeguarding the prisoner’s “personal safety” once they have been sprayed, citing “fresh air” and “copious amounts of water to flush out the eyes.”

In the video, Skelton tells another officer he “probably should” roll the window down. Records state five minutes and 55 seconds later, a window is cracked when a lieutenant shows up. In the video, you then hear a plea for help and water.

Officer Skelton told Internal Affairs he didn’t give Thomas water because he was “angry.” Other officers stated they did not have any water to give, even though they were at a gas station.

Thomas’s cousin, Michael Burgess, said Thomas is bipolar and schizophrenic.

“He’s not going to follow any orders police give him,” Burgess said. “It’s just erratic. You never know. You never know what might set him off.”

Throughout the body camera footage, officers including Skelton claim they responded to other calls about Thomas that day.

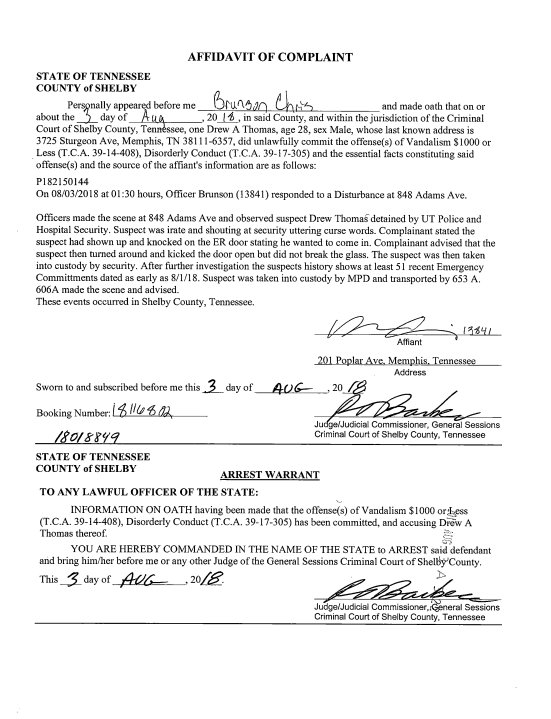

Later that night, he went to the hospital, then jail, where he’s no stranger. Court documents show a lengthy record including court-ordered mental evaluations and psychiatric treatments and programs.

A vandalism arrest report from August 2018 shows at that point, he had 51 recent emergency commitments.

Burgess said Thomas’s violence resulted in a restraining order. He says help is needed for his cousin. He’d like to see social workers assist in mental health calls, so officers don’t have to handle these situations alone.

“They should not have that responsibility,” he said. “When he’s not behaving or following orders, they’re going to naturally use force against him. And I don’t think that’s what should happen.”

Memphis officers respond to thousands of mental health calls each year

Memphis Councilman Jeff Warren says social workers assisting in certain mental health calls has come up in recent discussions.

“The issue is, how do you add social workers and mental health care workers into situations when needed and have the staff to do that?” he said.

MPD Director Michael Rallings says the force is already working to safely de-escalate and handle mental health crisis calls.

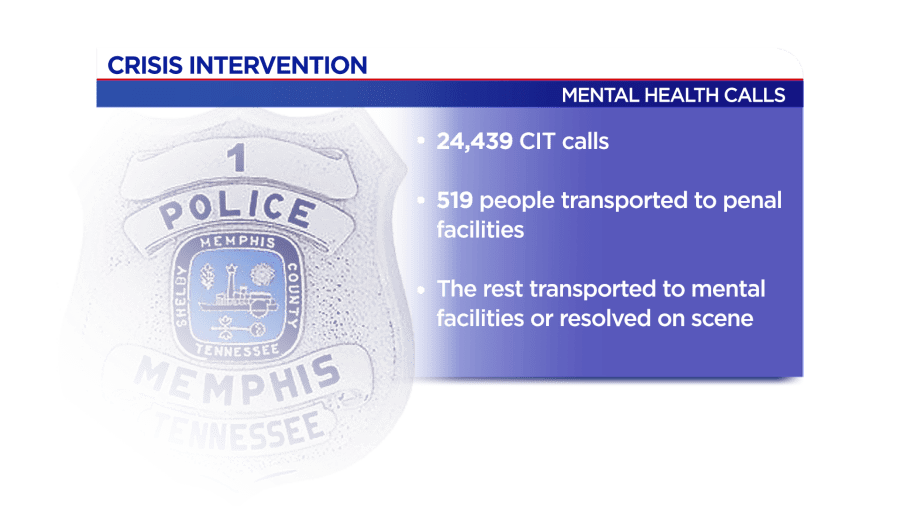

“Memphis is the international model for crisis intervention,” he said. “We have had the CIT program since the 80s.”

Rallings said every officer gets some training, but there are 268 officers currently active on the Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT. They volunteered and completed a 40-hour training program.

Rallings said ideally, he’d like to see more like 300 crisis intervention officers because last year, they responded to more than 24,000 calls.

“Yes. I would like to see more CIT officers, but we want them to volunteer,” he added. “Some say well, all of the officer should be specially trained and get the 40-hours of CIT. Some of our healthcare professionals don’t necessarily agree with that. They want to make sure we are selecting the officers that have the heart and compassion to do this work.”

He said crisis intervention officers have also partnered with social workers and paramedics to reach out to those who dial 911 the most for health related issues. They try to link them with a doctor.

Over the last several decades, he said, because there is a void of social workers and a void of access to health care, especially mental health, law-enforcement took over the mission.

“In the absence of those structures and those institutions, we know we have to respond to people who dial 911,” he said.

And until that capacity is there for social workers to respond and staffing levels are brought up to do the community policing that citizens have been asking for, Rallings said police have to rely on CIT.

“It’s our responsibility to do all we can,” Rallings said.

MPD said Skelton — as well as two other officers at the gas station that night — were on the Crisis Intervention Team.

Two officers received three-day suspensions for their actions that night.

Skelton was facing a number of charges including excessive force. He resigned before his administrative hearing.

Skelton told the Institute for Public Service Reporting he doesn’t want to comment on what happened. He is “happily working in the private sector.”

The case was never turned over to the District attorney’s office for review.

In an effort to be more transparent, MPD recently posted more information about the types of complaints made against officers over the past four years at https://reimagine.memphistn.gov/

About our partnership

One reason WREG, The Daily Memphian and the Institute for Public Service Reporting teamed up was to help defray the costs for internal files and body camera footage.

The city has charged close to $1,000 for some cases. It cost $252 to get the body worn camera footage in Thomas’s case.

Officials told us the price includes retrieving and redacting information required by law.