PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Hemp growers and entrepreneurs who were joyous a year ago after U.S. lawmakers reclassified the plant as a legal agricultural crop now are worried their businesses could be crippled if federal policymakers move ahead with draft regulations.

Licenses for hemp cultivation topped a half-million acres (200,000 hectares) last year, more than 450% above 2018 levels, so there’s intense interest in the rules the U.S. government is creating. Critical comments on the draft have poured in from hemp farmers, processors, retailers and state governments.

Growers are concerned the government wants to use a heavy hand that could result in many crops failing required tests and being destroyed. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, the agency writing the rules, estimates 20% of hemp lots would fail under the proposed regulations.

“Their business is to support farmers — and not punish farmers — and the rules as they’re written right now punish farmers,” said Dove Oldham, who last year grew an acre (0.40 hectares) of hemp on her family farm in Grants Pass. “There’s just a lot of confusion, and people are just looking for leadership.”

The USDA did not respond to the criticism but has taken the unusual step of extending the public comment period by a month, until Jan. 29. The agency told The Associated Press it will analyze information from this year’s growing season before releasing its final rules, which would take effect in 2021.

Agricultural officials in states that run pilot hemp cultivation programs under an earlier federal provision are weighing in with formal letters to the USDA.

“There are 46 states where hemp is legal, and I’m going to say that every single state has raised concerns to us about something within the rule. They might be coming from different perspectives, but every state has raised concerns,” said Aline DeLucia, director of public policy for the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture.

Most of the anxiety involves how the federal government plans to test for THC, the high-inducing compound found in marijuana and hemp, both cannabis plants. The federal government and most states consider plants with tiny amounts — 0.3% or less — to be hemp. Anything above that is marijuana and illegal under federal law.

Yet another cannabis compound has fueled the explosion in hemp cultivation. Cannabidiol, or CBD, is marketed as a health and wellness aid and infused in everything from food and drinks to lotions, toothpaste and pet treats.

Many have credited CBD with helping ease pain, increase sleep and reduce anxiety. But scientists caution not enough is known about its health effects, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last year targeted nearly two dozen companies for making CBD health claims.

Still, the CBD market is increasing at a triple-digit rate and could have $20 billion in sales by 2024, according to a recent study by BDS Analytics, a marketing analysis firm that tracks cannabis industry trends.

About 80% of the 18,000 farmers licensed for hemp cultivation are in the CBD market, said Eric Steenstra, president of the advocacy group Vote Hemp. The remaining 20% grow hemp for its fiber, used in everything from fabric to construction materials, or its grain, which is added to health foods.

But hemp is a notoriously fickle crop. Conditions such as sunlight, moisture and soil composition determine its ratio of THC to CBD. Choosing the right harvesting window is critical to ensuring it stays within acceptable THC levels.

Under the draft USDA rules, farmers have no wiggle room. They must harvest within 15 days of testing their crop for THC, and the samples must be sent to a lab certified by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Samples must be from the top of the plant, where THC levels are highest, and the final measurement must include not just THC, but also THCA, a nonpsychoactive component.

Crops that test above 0.3% for the two combined must be destroyed. Growers with crops above 0.5% would be considered in “negligent violation,” and those with repeated violations could be suspended from farming hemp.

In addition, a pilot program for federal crop insurance that would be available to hemp growers in some states specifies that crops lost because of high THC levels won’t be covered.

Those provisions are causing alarm among growers and states with pilot hemp programs allowed under the 2014 Farm Bill. Some states allow THC levels above 0.3%, and not all include THCA in that calculation. Many permit more harvesting time for growers after THC testing.

Farmers are lobbying for a 1% THC limit and a 30-day harvest window to give them more flexibility while remaining well under THC levels that can get people high.

The draft regulations don’t “seem to be informed by the reality of the crop,” said Jesse Richardson, who with his brother sells CBD-infused teas and capsules under the brand The Brothers Apothecary.

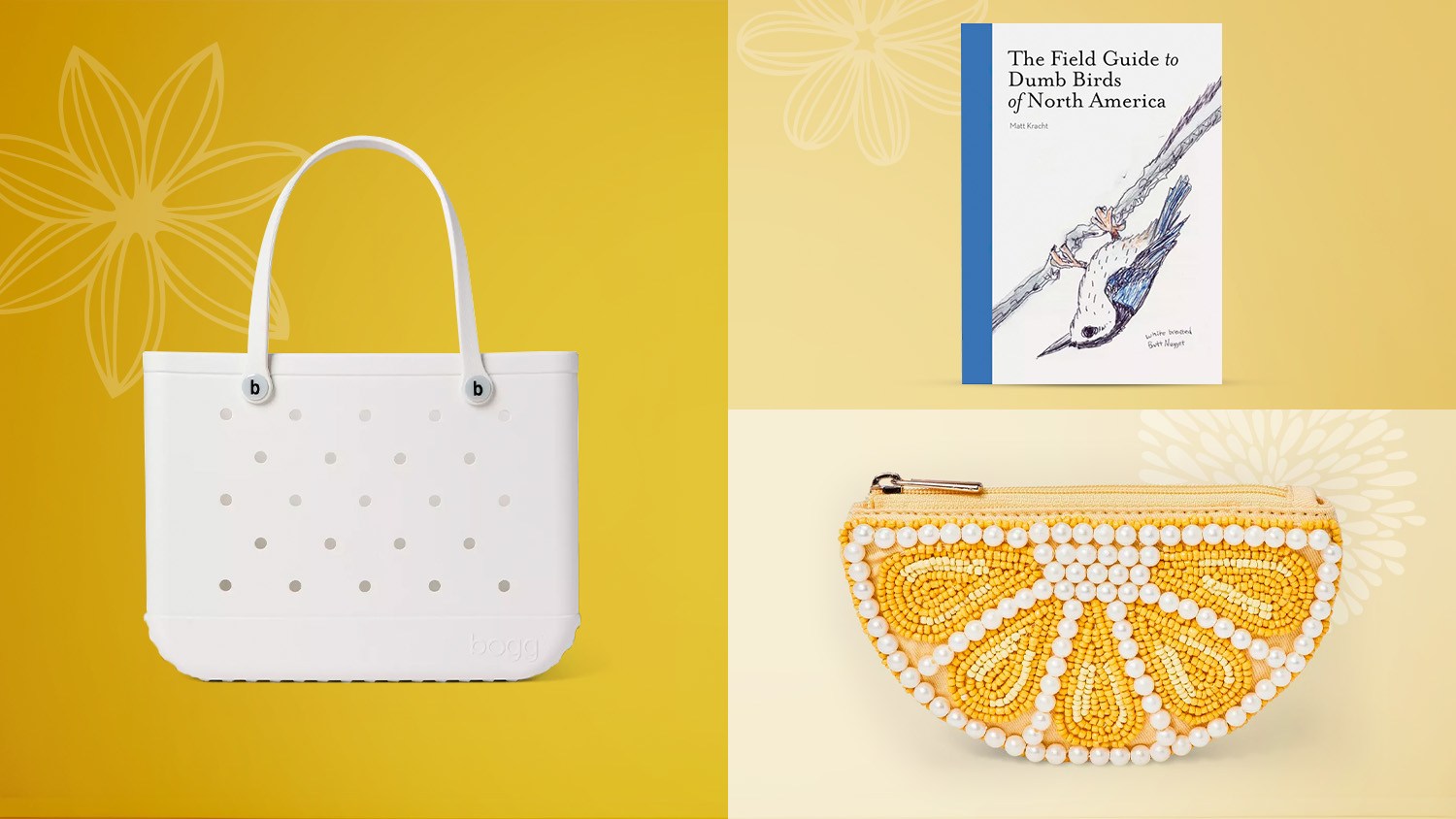

The Brothers Apothecary teabags made using hemp-derived CBD. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus)

“If no one can produce (federally) compliant hemp flower, then there will be no CBD oil on the market.”

Growers are also worried about the proposed rule requiring that all THC testing be done in a DEA-certified lab because there are so few of them. Some states have only one, which would serve hundreds of growers in a short harvest window.

Samantha Ford, a third-generation farmer in North Carolina, waited two weeks to get back THC results from a lab last fall and then spent 45 days harvesting her 1 acre (0.40 hectares) of hemp by hand.

“The 15-day window — that’s not feasible, and that was on a small scale,” she said. “I can’t imagine farmers who have acres and acres and acres of it.”

Concerns also have emerged about the workload the draft rules would place on states. Many do random sampling for THC levels, but the USDA would require five samples from every hemp lot — a burden for state agricultural departments, said DeLucia, of the national ag agencies group.

If federal rules are too onerous and expensive, some states might drop their hemp programs. In those cases, farmers would have to apply for licenses with the USDA, and at this stage it’s unclear how U.S. officials would manage or pay for a nationwide licensing program, DeLucia said.

Under the 2018 Farm Bill, the USDA must approve state plans for hemp programs. Louisiana, Ohio and New Jersey last month were the first to get the green light — but those plans might need to be reworked after final rules are written.

“What we don’t want to see is states having to write their rules and then have to change the rules again and rewrite them” after 2021, said Steenstra, of Vote Hemp.