MEMPHIS, Tenn. — A man says he came home from church and minutes later, a Memphis Police officer started using a stun gun on him with his hands cuffed behind his back.

The incident was uncovered in a joint investigation with the University of Memphis Institute of Public Service Reporting and The Daily Memphian as we work to uncover incidents of excessive force and help find solutions.

It was around noon on March 13, 2016. Antonio Strawder had just left church when he says Memphis Police Officer Otto Kiehl showed up outside his North Memphis home.

Kiehl was the same officer who had pulled Strawder over on the interstate a month earlier and gave him a citation for driving with a suspended license.

“I got out of the car,” Strawder recalled. “He was like, ‘Antonio did you ever get your license?’ I was like, ‘Nah.’ He said, ‘Come here.'”

Strawder said he went into the house but eventually agreed to walk outside. When he opened the door, he said, the officer was standing to the side of the door.

It’s unclear what happened next, since there was no body camera footage.

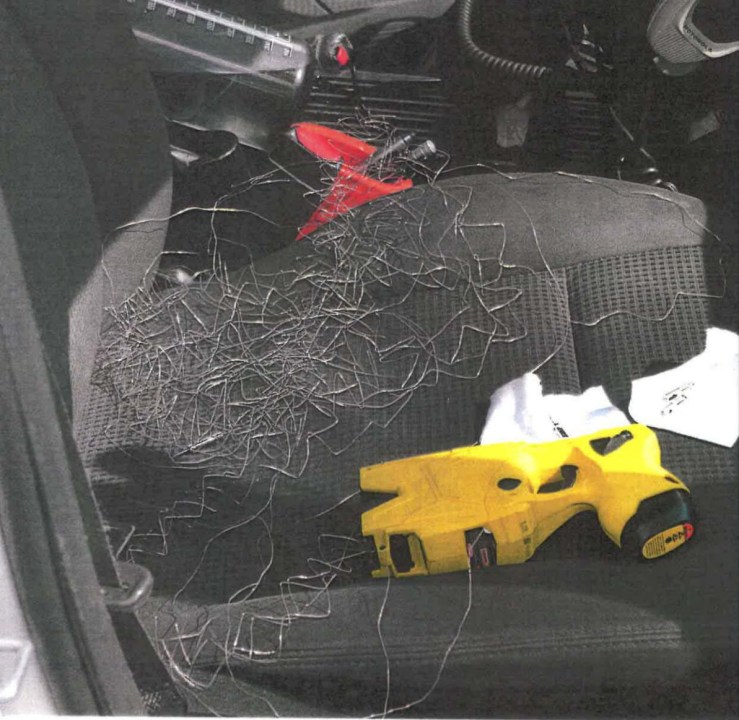

Strawder says he was handcuffed with his hands behind his back when Officer Kiehl fired his stun gun. One prong went into his back, the other in his leg.

“When he hit me with the Taser, I fell,” Strawder said.

That’s when Strawder’s girlfriend hit record on her cell phone.

Below: Video of Antonio Strawder being Tased by officers. WARNING: Graphic images

“There was this little puddle of water right there, so every time you hit the Taser, he would tell me to get up, and I would tell him, ‘I can’t move.'” Strawder said. “Every time I moved, he hit that Taser.”

Strawder was on the ground, still handcuffed, when the officer reportedly shocked him two more times.

“I was praying in my head that nothing else would happen,” he said.

Strawder was arrested for driving with a suspended license and resisting arrest. Paramedics removed the probes from his body.

When he made bond, he filed a complaint with MPD’s Internal Affairs department.

Officer Kiehl told Internal Affairs he was in the area that day and saw Strawder driving.

He said Strawder “snatched away” when he tried to get him in the squad car, so he used the stun gun on him. Kiehl said while he understood “the muscles lock up” when both prongs hit the body, he continued to shock him because he felt Strawder “was still resisting.”

The other officer seen in the video added that Strawder “was being very loud and shouting,” causing a crowd to form.

However MPD’s Internal Affairs ruled that Kiehl was in the wrong, suspending him for 10 days for excessive force and not obeying multiple sections of the weapons policy, like not giving “great care and consideration” to “any environment where the individual could fall” and get hurt. They also said the officer “should be aware” the “individual may not be able to respond to verbal commands during or immediately after” the shock.

MPD did not send the case to the district attorney’s office to determine whether the officer’s use of force was criminal.

Josh Spickler with Just City, a criminal justice reform advocacy group, said incidents like Strawder’s cause a rift and erode trust with the community.

“What this does to our community, it emphasizes that Black lives don’t matter,” Spickler said. “There again we have an officer standing over a Black man screaming in pain.”

By making these incidents public, Spickler said the community has a better understanding of what needs to change.

“That’s exactly the kind of thing that will build trust back in this community, that yes, you do matter. The Black lives we are mostly policing matter,” he said. “That’s one way to do it. Open this stuff up.”

Antonio Strawder is seen on the ground after an officer used a stun gun on him.

Officer Otto Kiehl

Stun gun after use

Strawder’s video and 410 pages of documents related to the case were obtained by the Institute for Public Service Reporting through an open records request.

After the incident, Officer Kiehl said MPD’s policy was “confusing.”

An MPD spokesperson said that training is received during basic recruit training and during annual in-service training and all officers with stun guns must re-certify annually. Officers can always ask questions.

Last month, Police Director Michael Rallings also stressed that the department offers more training than what’s required.

“There’s been demands on culture diversity, sensitivity, fair and just policing. We’ve got a whole laundry of course is that we already give it to our officers,” Rallings said.

MPD states training and policies are reviewed often and adjustments are made when necessary, but says no major changes have been made to policy.

Recently, in an effort to be more transparent, MPD helped launch a new website where that policy is posted and they explain how citizens can file complaints.

Kiehl, who left MPD in July, told the Institute for Public Service Reporting that he believes his actions that day were “tactically, legally and morally acceptable.”

“I had a very resisting suspect with half a dozen hostile family members at my back,” Kiehl said. “He didn’t listen to me.”

As for Strawder, he says what hurt the most that day is that his mother watched it unfold. Soon after, she died of cancer.

“That hurt her too, because anything could’ve happened,” he said.

Strawder was not found guilty of resisting arrest, but guilty of driving with a suspended license.

About our partnership

One reason WREG, The Daily Memphian and the Institute for Public Service Reporting teamed up was to help defray the costs for internal files and body camera footage.

The city has charged close to $1,000 for some cases. It cost $86 to get the video and 410 pages related to Strawder’s incident.

Officials told us the price includes retrieving and redacting information required by law.