JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — At Granny Shaffer’s restaurant in Joplin, Missouri, owner Mike Wiggins is reprinting the menus to reflect the 5, 10 or 20 cents added to each item.

A two-egg breakfast will cost an extra dime, at $7.39. The price of a three-piece fried chicken dinner will go up 20 cents, to $8.78. The reason: Missouri’s minimum wage is rising.

Wiggins said the price hikes are necessary to help offset an estimated $10,000 to $12,000 in additional annual pay to his staff as a result of a new minimum wage law taking effect Tuesday.

“For us it’s very simple. There’s no big pot of money out there to get the money out of” for the required pay raises, Wiggins said.

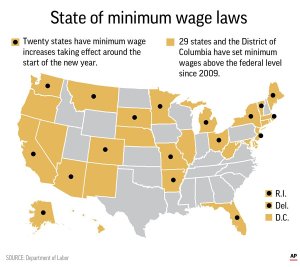

New minimum wage requirements will take effect in 20 states and nearly two dozen cities around the start of the new year, affecting millions of workers. The state wage hikes range from an extra nickel per hour in Alaska to a $1-an-hour bump in Maine, Massachusetts and for California employers with more than 25 workers.

Seattle’s largest employers will have to pay workers at least $16 an hour starting Tuesday. In New York City, many businesses will have to pay at least $15 an hour as of Monday. That’s more than twice the federal minimum of $7.25 an hour.

A variety of other new state laws also take effect Tuesday . Those include revisions to sexual harassment policies stemming from the #MeToo movement, restrictions on gun sales following deadly mass shootings and revamped criminal penalties as officials readjust the balance between punishment and rehabilitation.

The state and local wage laws come amid a multi-year push by unions and liberal advocacy groups to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour nationwide. Few are there yet, but many states have ratcheted up wages through phased-in laws and adjustments for inflation.

In Arkansas and Missouri, voters this fall approved ballot initiatives raising the minimum wage after state legislators did not. In Missouri, the minimum wage will rise from $7.85 to $8.60 an hour on Tuesday as the first of five annual increases that will take it to $12 an hour by 2023.

At Granny Shafffer’s in Joplin, waitress Shawna Green will see her base pay go up. But she has mixed emotions about it.

“We’ll have regulars, and they will notice, and they will bring it to our attention, like it’s our fault and our doings” that menu prices are increasing, she said. “They’ll back off on something, and it’s usually their tips, or they don’t come as often.”

Economic studies on minimum wage increases have shown that some workers do benefit, while others might see their work hours reduced. Businesses may place a higher value on experienced workers, making it more challenging for entry-level employees to find jobs.

Seattle, the fastest-growing large city in the U.S., has been at the forefront of the movement for higher minimum wages. A local ordinance raised the minimum wage to as much as $11 an hour in 2015, then as much as $13 in 2016, depending on the size of the employer and whether it provided health insurance.

A series of studies by the University of Washington has produced evolving conclusions.

In May, the researchers determined that Seattle’s initial increase to $11 an hour had an insignificant effect on employment but that the hike to $13 an hour resulted in “a large drop in employment.” They said the higher minimum wage led to a 6.9 percent decline in the hours worked for those earning under $19 an hour, resulting in a net reduction in paychecks.

In October, however, those same researchers reached a contrasting conclusion. They said Seattle workers employed at low wages experienced a modest reduction in hours worked after the minimum wage increased, but nonetheless saw a net increase in average pretax earnings of $10 a week. That gain generally went to those who already had been working more hours while those who had been working less saw no significant change in their overall earnings.

Both supporters and opponents of higher minimum wages have pointed to the Seattle studies.

The federal minimum wage was last raised in 2009. Since then, 29 states, the District of Columbia and dozens of other cities and counties have set minimum wages above the federal floor. Some have repeatedly raised their rates.

“The federal minimum wage has really become irrelevant,” said Michael Saltsman, managing director of the Employment Policies Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based group that receives funding from businesses and opposes minimum wage increases.

The new state minimum wage laws could affect about 5.3 million workers who are currently earning less than the new standards, according to the liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute, based in Washington, D.C. That equates to almost 8 percent of the workforce in those 20 states but doesn’t account for additional minimum wage increases in some cities.

Advocates credit the trend toward higher minimum wages to the “Fight for $15,” a national movement that has used protests and rallies to push for higher wages for workers in fast food, child care, airlines and other sectors.

“It may not have motivated every lawmaker to agree that we should go to $15,” said David Cooper, senior economic analyst at the Economic Policy Institute. “But it’s motivated many of them to accept that we need higher minimum wages than we currently have in much of the country.”